Dialing

in on the Downy:

Dealing with Basil Downy Mildew in your Greenhouse

By Dr. Natalie Bumgarner

|

| http://hyg.ipm.illinois.edu/article/php?id=467 |

Some

basic facts on basil downy mildew

Basil downy mildew (Peronospora belbahrii) is a disease that

is rapidly getting the attention of many of hydroponic greenhouse growers. Over

the last couple months, we have heard from growers in several states who are

now facing this disease. So, I want to take an opportunity in this blog to introduce

growers to the threat and present some information as well as sites for further

research. Knowledge and preparation are some of the best steps to prevent or

mitigate losses in our greenhouse

basil crops.

In the continental US, reports of basil downy mildew

were first confirmed in late 2007 and the disease has been widely distributed

from 2008 onward. Significant crop losses in both outdoor and greenhouse

production have been reported since that time for a couple reasons. First, a

new disease situation can be a challenge because growers are less prepared for

the appearance of a relatively new disease and the development of chemical or

other control measures likely are not complete from a broad industry perspective.

Secondly, any infection on the leaf can result in unmarketable crop due to

appearance and rapid deterioration after harvest, so losses can mount

quickly.

Tracking

its spread

Basil downy mildew can be spread through seeds or

airborne spores, so the disease can affect crops from multiple sources. Work is

underway to develop and implement accurate tests to identify the pathogen on

seeds and enable sale of disease-free basil seeds. This will be crucial to more

effective control of the pathogen in the future, but growers must also be

vigilant in terms of the threat from airborne spores. The pathogen can

overwinter in warm areas (such as southern Fl) and can be distributed through

airstreams as the growing season progresses. This means that the incidence and

frequency of infection often moves northward during the late spring and summer

months. Monitoring and reporting programs are available for growers to be

better aware of when outdoor or greenhouse crops in their area have been

reported with basil downy mildew. The first site listed in the additional

information section at the end of this blog has info on the monitoring program.

Recognizing

the signs

Early symptoms can mirror nutrient deficiency, so it is

important to check for fungal growth under the leaf, which can develop only 2

to 3 days after infection.

The

stages of impact

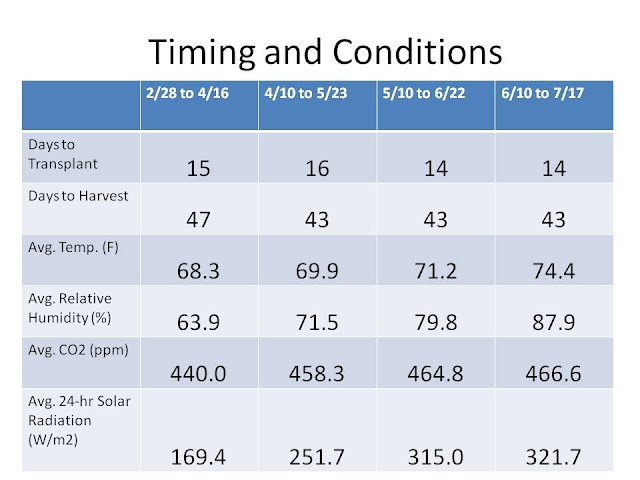

The image on the left illustrates early stage infection while the plant on the right has a more severe infestation that render the entire plant unmarketable in addition to producing spores that will likely infect nearby plants. Impacts in a greenhouse can be severe as the pathogen can spread quickly under greenhouse temperature and humidity ranges because they are conducive to rapid multiplication.

Preventing

disease

Preventative steps fall into two main categories for

growers. The first occurs in seed and cultivar selection. As discussed earlier,

disease free seed is going to become increasingly available in the future.

Additionally, it has been demonstrated in various tests that sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum) is the most

susceptible to basil downy mildew. Red leaf basil as well as Thai basil and the

lemon and lime basils have generally been shown to be more resistant than sweet

basil.

The second important element in preventing the disease

is controlling the environment in your greenhouse to minimize conditions that

lead to the reproduction and spread of the disease. It will be crucial in the

prevention and control of the disease to reduce leaf wetness by maintaining

lower relative humidity and increasing air flow in the greenhouse. Such steps

can include maintaining slightly higher temperatures to reduce relative

humidity, increased lighting (or decreased shading), as well as increasing air

circulation through addition of fans or some other method.

Control

options

First step- Assess the extent of

infection

The

important first step in addressing basil downy mildew is to determine the

severity of infection. In some cases, removing the most affected plant material

from the greenhouse may be needed as remediation of affected tissue is

challenging. Infected plants often are completely unmarketable and may pose

more risk than reward if left in the greenhouse. In some instances, the removal

of a few plants may be adequate if the disease is caught in the early stages.

How much of the crop with mild to moderate infection that should be removed is

kind of a judgment call, but this is not known as an easy disease issue to

control. Another step that can help if the older plants are highly infected is

starting new seedlings in a separate area where the inoculum cannot

spread to them from the older plants while you are spraying to control the disease

Second step- Decide on a control

approach

Spray

and chemical options: There are not as many weapons as we might like in terms

of spray materials for use in greenhouses for basil downy mildew, but there are

a few tools at our disposal. Another thing to keep in mind is that these

controls have been shown to be more effective as a preventative, so spraying to

prevent infection on the plants that are still healthy is one of the most

important goals.

In the organically certifiable or softer category, there are hydrogen dioxide products (Oxidate), biologicals (Actinovate) as well as potassium bicarbonate (Milstop) products. These are labeled for use in greenhouses and on downy mildew, but in tests have not generally been the most effective materials for controlling active infections.

In terms of conventional fungicides, some products that have been listed as most effective and labeled for greenhouse use are cyazofamid (trade name Ranman), phosphanates (trade names such as ProPhyt, Fosphite, and Fungi-Phite) and others detailed in the additional resources. It is best to alternate use of chemicals to try and prevent pathogen resistance. Further information of specific chemical products and

In the organically certifiable or softer category, there are hydrogen dioxide products (Oxidate), biologicals (Actinovate) as well as potassium bicarbonate (Milstop) products. These are labeled for use in greenhouses and on downy mildew, but in tests have not generally been the most effective materials for controlling active infections.

In terms of conventional fungicides, some products that have been listed as most effective and labeled for greenhouse use are cyazofamid (trade name Ranman), phosphanates (trade names such as ProPhyt, Fosphite, and Fungi-Phite) and others detailed in the additional resources. It is best to alternate use of chemicals to try and prevent pathogen resistance. Further information of specific chemical products and

tests of their relative efficacy are available at many of the sites listed in the additional resources section

Third step- Watch the disease closely

and keep on top of the spray schedule

Remember, this disease is most effectively prevented

rather than controlled. So, there is a need to spray both for control and

prevention under conditions that are most conducive to the disease. One thing

to keep in mind as you implement your control plan is that a backpack

sprayer is going to be difficult to get

adequate leaf coverage because the underside of the leaf is where the pathogen

is most present. If frequent spraying is needed, it is worth considering acquiring some type of air assisted mist blower or high

pressure cold fogger.

Arming ourselves with information, remaining vigilant in

environmental control and scouting and acting quickly if disease is found are

all key in managing the risk of basil downy mildew in our greenhouse crops.

Additional

information

http://vegetablemdonline.ppath.cornell.edu/NewsArticles/BasilDowny.html

http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pp271

http://hyg.ipm.illinois.edu/article.php?id=467

http://www.greatplainsgrowers.org/2012%20program/Powerpoints/MeganKennellyVegDiseaseHeadlines.pdf

http://extension.umass.edu/vegetable/articles/downy-mildew-basil